A common bacterium that more than half of people have in their gut can use hydrogen gas present in the gastrointestinal tract to inject a cancer-causing toxin into otherwise healthy cells, according to a recently published study led by UGA researchers.

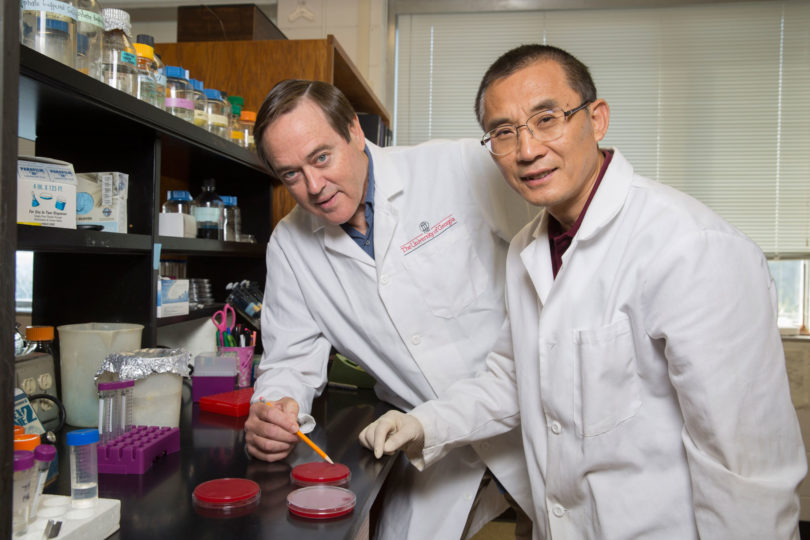

The bacterium’s reliance on hydrogen presents a pathway to potential new treatment and preventive measures in fighting gastric cancers, which kill more than 700,000 people per year, said corresponding author Robert Maier, Georgia Research Alliance Ramsey Eminent Scholar of Microbial Physiology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences.

Previous studies solidified the relationship between stomach ulcers, cancers and certain strains of Helicobacter pylori, a stomach-dwelling bacterium that causes 90 percent of all gastric cancers. Earlier research also found a link between a toxin known as CagA, or cytotoxin-associated gene A, and cancer formation. But the new study exposes how the bacterium uses hydrogen as an energy source to inject CagA into cells, resulting in gastric cancer, Maier said.

“There are many known microbes in the human gut that produce hydrogen and others that use hydrogen. The implications of the study are that if we can alter a person’s microflora, the bacterial makeup of their gut, we can put bacteria in there that don’t produce hydrogen or put in an extra dose of harmless bacteria that use hydrogen,” Maier said. “If we can do that, there will be less hydrogen for H. pylori to use, which will essentially starve this bacteria out and result in less cancer.”

Although many people carry the H. pylori bacterium, it can take decades for the infection to develop into cancer, providing an opening for aggressive preventive measures in people who have a high risk of developing tumors, said lead author Ge Wang, a senior research scientist in Franklin College’s microbiology department. The presence of H. pylori strains with both CagA and high hydrogen-utilizing activity within patients can potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting future cancer development.

“If hydrogen is in the gastric mucosa, of course a bacterium will use it,” Maier said. “It’s an excellent energy source for many bacteria out in nature. But we didn’t realize that pathogens like H. pylori could have access to it inside an animal in a way that enables the bacterium to inject this toxin into a host cell and damage it.”

The study, “Hydrogen metabolism in Helicobacter pylori plays a role in gastric carcinogenesis through facilitating CagA translocation,” was recently published in the American Society for Microbiology journal mBio and was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Georgia Foundation. It is available online at http://tinyurl.com/jxt485q.